Part One |

Contributions to Meteorology ~ by ~ Bob Gilbert |

Signal Service |

|

After Confederate forces surrendered in 1865, the Signal Corps faced the same prospect of deactivation as many other Union Army regiments while its founder, Colonel Albert J. Myer, challenged the unlawful revocation of his promotion and appointment as Chief Signal Officer. Colonel Myer's lawyers won his case because no justification had been submitted to rescind a unanimously recommended reward for commendable service. As the victorious CSO reported for duty in 1867, a crisis was developing in the region where he grew up which was destined to save his corps that had influenced many battles and campaigns and vastly improved ship-to-shore communications.

The Great Lakes were just as indispensable to the region's commerce each summer as they were dangerous to mariners whenever winter approached. November was clearly the most hazardous time of the year for the expanding fleet of almost 3,000 ships and smaller craft. A marine editor in Wisconsin recorded each nautical accident in the region during 1868 and 1869, and this "casualty report" appeared in the December 8, 1869 issue of the Milwaukee Sentinel. Seemingly endless lists of vessels in distress galvanized a meteorologist employed by the Smithsonian Institution who had advocated a national storm telegraph warning service for many years.

|

Professor Increase Allen Lapham immediately started a petition addressed to his Congressman. Although fewer than three thousand ships comprised the regional fleet, here was evidence of 3,078 accidents, 530 deaths, and more than $7 million in property losses in just two years. There was no shortage of experienced Smithsonian weather observers throughout the country to warn the public of approaching storms. The U.S. Army Medical Service had been investigating possible connections between human health and weather patterns since the War of 1812. Nautical charts produced by the U.S. Naval Observatory showed the world's mariners where wind and ocean currents combined to make their ships faster than ever before possible. The U.S. Coastal Survey was the largest employer of scientists in the country, and had made many important discoveries since its inception in 1807. "Wisconsin's First Scientist" implored Representative Halbert Eleazer Paine to consider, "...the duty of the government...to prevent at least some portion of this sad loss in future."

|

General Paine was respected for preventing Baton Rouge, Louisiana from being needlessly destroyed during the Civil War, and Lapham's petition rekindled this concern for life and property. The general composed H.R. 602 and introduced it to Congress more than a week before Christmas of 1869. Shortly thereafter, Paine received a visitor from the Signal Service, which is how the Signal Corps had been renamed after being reduced in size. Colonel Myer boldly pursued a chance to put the new weather service together despite a complete lack of telegraph lines, weather instruments, or a trained staff of certified meteorologists. His headquarters was no larger than a small row house in downtown Washington, DC, and his only relevant experience was taking weather observations as an Army doctor at Fort Duncan, Texas a few years before the war.

No records were kept of what Myer and Paine discussed, but it must have been a productive meeting. The Army Medical Service had about fifty years' experience monitoring the weather. Professor Joseph Henry's Smithsonian Institution had been archiving weather data and printing its own weather maps for twenty years. The U.S. Naval Observatory boasted the achievements of "The Pathfinder of the Seas," Commodore Mathew Fontaine Maury, whose nautical charts saved the world's ship companies fortunes by dramatically shortening trans-Atlantic voyages. Foreign-trained astronomer Professor Cleveland Abbe had just recently pioneered the art of forecasting the weather for the general public within a 100-mile radius of Cincinnati, Ohio.

Interestingly, seven weeks after President Ulysses S. Grant signed Paine's unanimously passed bill into law on February 9, 1870, the Signal Service had been appointed by the Department of War to report weather conditions and issue warnings for the "northern lakes and Atlantic Coast." This selection spoke volumes about the confidence in what Paine referred to as "military discipline," but more importantly, what the Signal Corps accomplished during the recent war. America and many nations around the world connected by telegraph lines would benefit immeasurably by having an army officer of Albert Myer's caliber named as founding director of America's first federal storm warning service.

|

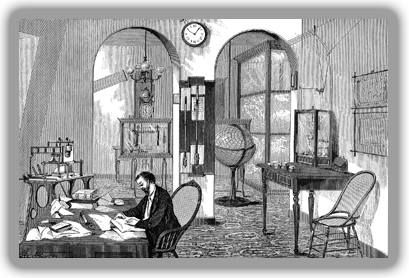

Contracts with civilian telegraph companies such as Western Union enabled the Signal Service to transmit storm warnings faster than storms travelled. Myer the cryptologist developed a brevity code to reduce charges assessed by telegraph companies according to the length of messages and the distances they were sent. The best weather instruments made by astronomical observatories in the United States, Russia, Ireland, England, and Italy arrived at the newly leased four-story headquarters building at 1719 G Street. America's first school specifically designed to train meteorologists opened at Fort Whipple, next to Arlington National Cemetery. The syllabus was developed by textbooks from the Chief Signal Officer's library written by the world's leading scientists. Before the first graduating class reported for duty at 25 stations mostly located east of the Rocky Mountains, Myer wrote, "the idea of a world-wide system of telegraphic weather reports is not nearly as chimerical to-day as was thirty years ago the workings of the telegraph itself."

Brevet Brigadier General Albert Myer wasn't at his HQ on opening day, which was chosen with the Great Lakes mariners' worst threat in mind. He was in Buffalo on November 1, 1870, to evaluate how well a typical station coordinated its reports with headquarters at 7:35am, 4:35pm, and 11:35pm. It wasn't long before duty called him away to Chicago, where the city's location in the path normally followed by storms crossing the continent from the west made it an ideal warning center for the region. The general hired Profesor Lapham of Milwaukee as his assistant just in time for this civilian to write the federal government's first official storm warning on November 8th. History had been made, and the director was part of the process when the Chicago office telegraphed the message to the Great Lakes mariners.

|

|

Adversity struck not long after operations began. Professor Lapham could not be expected to continue his vital work and execute the Will of his deceased friend Byron Kilbourn in Florida, who brought the scientist to Wisconsin to build a commercial waterway that never materialized. Another qualified assistant needed to be found. General Myer then lost the cooperation of Western Union when its president tried to monopolize all government telegraph services, for which William Orton demanded payment in advance. Last minute pleas for public safety fell on deaf ears, and Western Union's services were not restored until after the Attorney General intervened. Ironically, the birth of the federal weather service ended Professor Cleveland Abbe's operation in Cincinnati, so he was the natural choice to write forecasts for General Myer and train army officers to predict the weather. Four months after Abbe reported to Washington, DC, The New York Herald became the first American newspaper to print a nationwide weather forecast on May 5, 1871, and the general inherited a new nickname.

Forecasts were entitled "The Probabilities," so the media began praising "Old Probabilities" whenever good weather arrived or when forecasts were fulfilled. These early predictions verified approximately eighty percent of the time despite very limited technology. General Myer also bore the ridicule of newspaper editors and humorists like Josh Billings and Mark Twain whenever a forecast failed, and took the blame for bad weather. The media preferred the shorter title "Weather Bureau" to Myer's lengthy "Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce and Agriculture," and this nickname persisted well into the twentieth century. Overall, the general public seemed very satisfied with the revolutionary service and described a futuristic society confidently planning its outdoor activities 24-36 hours in advance according to what "Old Probs" said. Construction workers, steam boat crews, farmers, and railroad workers increased the demand for meteorological services. What began as a regional storm warning network was rapidly becoming a fully capable national weather service. (see: July 31, 1874 "Probibilities")

|

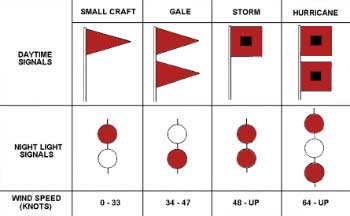

The red signal flag with the smaller white square center was altered with a black center to warn mariners of severe weather. General Myer called it the "Cautionary Storm Signal" and the station at Oswego, New York displayed it for the first time in October of 1871. A red light at night served the same function at port cities around the United States. As 1872 dawned, the Weather Bureau assumed a new international dimension by exchanging daily weather reports with Canada thanks to Professor George T. Kingston's University of Toronto Observatory. Almost 100 weather stations ringed the continent to warn of approaching severe weather by the start of 1873. Expansion seemed endless.

Five army "upper air" weather stations including Mount Washington, New Hampshire and Pikes Peak, Colorado systematically studied the upper levels of the atmosphere for the first time in American history. Sergeants and privates assigned to the mountain stations endeared themselves to their chief for enduring hardships like exposure, hypothermia, and in some cases, altitude sickness. Myer accepted data gathered by civilian balloonist Samuel Archer King and hundreds of volunteer observers sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution. By the time that a highly detailed lithograph of General Myer appeared on the front page of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in August of 1873, "Old Probs" was traveling to Europe.

The Austrian government invited him to attend the first congress of the International Meteorological Organization, or IMO, which is called the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) today. Thirty-two delegates representing twenty countries gathered in Vienna at the brand new facility built for the Zentralanstalt für Meteorologie und Geophysic (ZAMG). (NOTE: "The congress was planned at ZAMG on Hohe Warte Street, but the delegates actually met at the Austrian Academy of Sciences). These masters of many sciences hoped to standardize reporting procedures, forms used for archiving data, weather map symbols, and equipment used for measuring atmospheric elements such as temperature, wind speed and force, and rainfall. The most idealistic members hoped to route enough commercial ships away from storms to convince governments that there was more to lose by going to war than there was to gain from scientific cooperation.

|

General Myer's resolution to establish one daily weather observation taken by as many observers as possible around the world at the same moment in time passed without a single dissenting vote. The trans-Atlantic telegraph cable would soon start carrying weather reports taken at 7:35am to Signal Service headquarters from as far away as Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Australia. Meteorologists around the world synchronized their clocks to Washington, DC time, since Greenwich Mean Time had not yet been conceived. The Chief Signal Officer would spend the rest of his life encouraging the growth of this global network, no matter what the cost to his health.

Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes shared this dream for an international weather service, "...reaching to the good of all," not just the United States, or any other nation more so than another. Kate and Albert Myer were invited to White House dinners and socialized with dignitaries from many nations, some of which joined the international weather service. The Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia during the summer of 1876 was the perfect stage to advocate international scientific cooperation, and a Signal Service exhibit was built for that purpose. A handbill advertised, "Old Probabilities will reveal the secrets of his trade, and with the help of lighthouses and fog-signals show us the pleasant paths of peace." About a quarter of a million spectators enjoyed the spectacular opening ceremony; General Myer got blamed for afternoon rains that kept attendance down two days later.

Correspondence poured into Myer's office from a host of world-class scientists, most notably Lord Kelvin in Glasgow, Scotland, whose electronic device rescued the trans-Atlantic cable upon which the international weather service depended. The French astronomer, Urbain J.J. LeVerrier, who discovered Neptune in 1846, Austrian climatologist Julius Hann, Norwegian polar explorer Henrik Mohn, Scottish meteorologist Alexander Buchan of Edinburgh, and the chief of the British Met Office, Robert Henry Scott in London added their support. So did the first three IMO Presidents; C.H.D. Buys-Ballot in Utrecht, Eletheure Mascart in Paris, and Heinrich Wild in St. Petersburg, Russia. Particularly helpful was a group of Jesuit priests led by the "Father of Astrophysics," Father Angelo Pietro Secchi from his astronomical observatory at the Vatican in Rome. Father Marc Dechevrens reported from the Zikawei Observatory in Shanghai, China, and Father Frederico Faura saved many lives predicting typhoons approaching the Philippine Islands. Father Benito Vines earned the moniker "Father Hurricane" for his work at the Belen University Observatory in Havana, Cuba. It was clear that the Signal Service would need a bigger building just for storing paperwork alone.

|

So much data from military and civilian sources on land and at sea made it possible to track storms crossing continents and oceans for the first time in world history on colorized weather maps of the northern hemisphere. It was a giant leap from the first Weather Bureau maps which were very plain black and white outlines of the United States by itself, and an extension of a color scheme started in early 1872. (see: June 3, 1873 Weather Map) The United States and parts of Canada were lithographed in a light brown hue with darker brown markings representing mountain ranges in order to study geographical effects upon weather. The daily hemispheric maps begun on July 1, 1878 complemented the daily international weather bulletins that had already been distributed for three years. (see: October 1877 World Weather Map)

General Myer was equally proud of the fast response to shipwrecks along the North Carolina coast during the winter of 1877-1878. Observer-sergeants and their assistants at Kittyhawk, North Carolina coordinated the rescue of stranded vessels in the middle of the night with a storm in full force. The same flag signal system used in war helped alert life-saving station crews, lighthouse keepers, and salvage ship captains. Not only could the crew of the stranded ship get rescued faster, but the vessel in distress could be pulled away from the surf before it was irreparably damaged. This winter was also the debut of a square white and black flag to warn mariners that although a storm had passed and the sky appeared to be clearing, high winds in the storm's wake had the potential to cause dangerous currents and waves.

Government studies proved that Myer's methods were successful, and since fully loaded cargo ships were so valuable at that time, only a few ships needed to be saved from weather-related disasters to justify the Signal Service budget. One-third of American homes received daily forecasts thanks to cooperation from newspapers, and predictions were posted at thousands of railroad stations, post offices, and telegraph offices across the country. General Myer's fame grew and his nickname appeared on a play written by Mathew Wheeler even though forecasts had been renamed "indications." The international weather service had grown to include 36 countries, and a second IMO congress was scheduled for April, 1879 in Rome, Italy.

The delegates in Rome were disappointed by General Myer's absence, but it was only due to Congress being in recess until it was too late to approve his travel. Doctors and politicians urged the general to go to Europe anyway for much needed rest, although daughter Kate and Albert Jr. went with their father, his work took priority. A grateful king thanked the general for improvements made to Italy's weather service, but a doctor had to tend to the overworked visitor in Venice. Myer may have returned home much weaker than before, but there was much to celebrate. The Daily Graphic of New York City started a lasting trend by printing a daily weather map on May 9th and Private John Park Finley's tornado research eclipsed that of any other American; his rules for predicting tornado outbreaks set an impeccable standard. The U.S. Government Patent Office awarded Myer his third patent in June. (Myer's Third Patent)

|

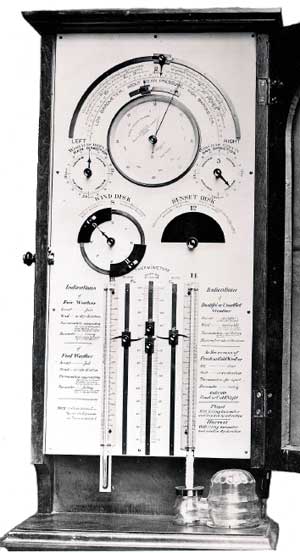

This latest invention was a combination weather instrument intended to help farmers predict the weather. The "Farmer's Weather Case," contained a barometer, a thermometer for measuring the temperature and a second, modified thermometer to measure the moisture content of the atmosphere, and wind dials pertaining to the direction. Adjustable pointers helped the farmers predict future changes in weather conditions after registering changes on the instrument noticed during the previous twenty-four hours. America was still so rural in many places at this time that farmers simply did not receive newspapers and did not frequent post offices, telegraph offices, or railroad stations where forecasts were updated.

By 1880, it was obvious that the Signal Corps founder was dying without having been formally recognized or rewarded by the U.S. Army for all of this progress. He had been paid as a Colonel, but allowed to wear a Brigadier General's star according to the brevet system then in effect. Slightly more than a month before he died, his promotion to Brigadier General without the brevet "asterisk" was announced. He was welcomed as a member of the geographical societies of the United States, Quebec, and Italy. The Austrian Meteorological Society and Natural Science Society of Emden awarded him honorary memberships.

Newspapers from every section of the United States announced his death and printed lengthy "biographical sketches," and the funeral procession in Buffalo reflected how popular he had become. The Popular Science Monthly, not normally noted for paying tribute to fallen generals, eulogized Albert Myer with a 4-page article and a full-page lithograph. Phrases like, "His legacy is a grand one ... the glory of having originated one of the grandest ideas of the century ... which has already saved many lives ... a revolution in the science of meteorology ...," were not exaggerated at all. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper concluded its obituary with, "...his fame is sure, since it rests on solid achievements in the interest of all mankind." Myer's successor, General William B. Hazen, claimed that, "no man in the Army had done as much original work..." His legacy can still be seen today.

|

General Myer didn't write a single "law of storms" unlike theoretical meteorologists of his day. It was far more important to determine the storm's location, strength, speed and direction of movement, and warn the public in time to save lives. Therefore, it is not surprising that his legacy pertains to practical meteorology. Many procedures he established have been honored with the passage of more than a century. American newspapers continue to print daily weather forecasts and weather charts. Weather observations are still taken around the world at regular intervals with standardized equipment and reported in a standard code in order to transcend language barriers. Only the nature of the technology used has changed. Fifty countries and groups of islands belonged to the IMO in 1880; by the year 2000, the World Meteorological Organization headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland claimed 185 participants. The chart of the northern hemisphere that debuted in 1877 was used well into the twentieth century, long after the weather service was transferred from the U.S. Army to the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1891.

The visual storm warning system of flags and lights begun by General Myer was expanded after his passing and endured until radio made it obsolete in the 1920s. Flags of different shapes, sizes, and colors displayed above prominent buildings around the country told the public what to expect in terms of severe storms and other conditions such as fair weather, warming or cooling trends, damaging winds, and widespread or localized, showery precipitation. Perhaps the most lasting tribute to Myer's visual warning system is the square "red and black" (Hurricane Flag) waving above beaches and marinas today. This is noteworthy when considering advances in satellite communications and the termination of its use by the National Weather Service in 1989.

Not everything of what General Myer started exists as it was. Weather Bureau functions were taken from the U.S. Army and given to the Department of Agriculture in 1891, followed by yet another transfer to the Department of Commerce in 1940. In the 1990s, the National Weather Service eliminated weather observing as a viable career path, and the Federal Aviation Administration began funding government contractors for what is still considered a safety issue. No matter how sophisticated lasers and sensors produced by the NWS have become, human observers are still needed at America's airports to verify the accuracy of the data and compensate for equipment limitations. Volunteer civilian observers are still relied upon by the NWS, and are eligible for an Albert J. Myer Award after 65 years' service.

Exceeding a 90% verification rate for forecasts, warnings, watches, and advisories is still as elusive in the 21st Century as it was in the 19th, but significant strides have been made in other ways. General Myer's staff could only forecast weather conditions at the earth's surface twenty-four to thirty-six hours into the future, but the NWS predicts changes from the surface to 20,000 feet seven days into the future. Whereas forecasts and warnings failed to verify due to an incomplete understanding of the atmosphere or because there wasn't enough information to process, too much information creates challenges today. So many computer models have to be compared at the beginning, middle, and end of the forecast period that it is difficult to become accustomed to the peculiarities of each model under various conditions. Choosing which model to use for each part of the forecast period in time to meet deadlines set for each weather report to be issued is not as easy as it may seem.

|

Ironically, the superior performance award given by the National Weather Service does not bear the name of the organization's founding director, but rather the forecaster in charge of the Galveston, Texas office during the hurricane of 1900. It is the coveted Isaac Cline Award adorned with two square, "red and black" flags for which NWS employees and offices compete each year. A privately-funded wood carving statue resembling General Myer was made by "Carvings for a Cause" in 2010 using a tree that fell during a stowstorm (The October Surprise). The statue will help pay for new trees that will be planted in Buffalo to replace those lost in the October 2006 storm.

The U.S. Army Signal Corps, which has honored its founder in many ways, trains its meteorologists at Fort Sill, Oklahoma to meet the needs of artillery units. A small group of Signal Corps officers and sergeants formed the nucleus of the U.S. Air Force Air Weather Service before World War II, just in time to meet the global demands of aviators flying in a variety of climates in every theater of the conflict. The weather school that was opened in 1870 next to Arlington National Cemetery was closed in the 1880s, but Fort Myer achieved prominence as home to Army Chiefs of Staff.

It is a lasting tribute to General Albert J. Myer that he was not only able to preserve the Signal Corps, but succeeded in finding a mission beneficial to his native state, region, nation, and the world in a military and civilian capacity that has endured long after his passing.

Also See: "Old Probabilities" Albert Myer and the US Weather Bureau

by Bob Gilbert

WNY Heritage Magazine ~ Winter 2010

|