| |

"No orders ever had to be given to establish the telegraph." Thus wrote General Grant in his memoirs. "The moment troops were in position to go into camp, the men would put up their wires." Grant pays a glowing tribute to "The organization and discipline of this body of brave and intelligent men."

|

|

THE MILITARY~TELEGRAPH SERVICE

By A. W. GREELY

Major-General, United States Army

| |

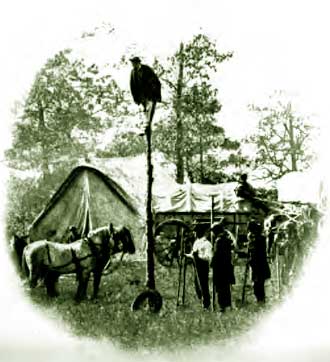

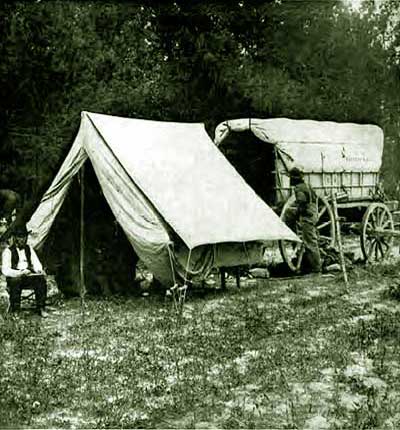

AT THE TELEGRAPH TENT, YORKTOWN ~ May, 1862

These operators with thier friends at dinner look quite contented, with their coffee in tin cups, their hard-tack, and the bountiful appearing kettle at their feet. Yet their lot, as McClellan's army advanced toward Richmond later, was to be far from enviable. "The telegraph service," writes General A.W. Greely, "had neither definite personnel nor corps organization. It was simply a civilan bureau attached to the quartermaster's department, in which a few of its favored members received commissions. The men who performed the dangerous work in the field were mere employees-mostly underpaid and often treated with scant consideration. During the war there occurred in the line of duty more than three hundred casualties among operators-by disease, killed in battle, wounded, or made prisoners. Scores of these unfortunate victims left families dependent on charity, for the Government of the United States neither extended aid to their destitute families nor admitted needy survivors to a pensionable status."

| |

|

|

|

The exigencies and experiences of the Civil War demonstrated, among other theorems, the vast utility and indispensable importance of the electric telegraph, both as an administrative agent and as a tactical factor in military operations. In addition to the utilization of existing commercial systems, there were built and operated more than fifteen thousand miles of lines for military purposes only.

Serving under the anomalous status of quartermaster's employees, often under conditions of personal danger, and with no definite official standing, the operators of the military telegraph service performed work of most vital import to the army in particular and to the country in general. They fully merited the gratitude of the Nation for their efficiency, fidelity, and patriotism, yet their services have never been practically recognized by the Government or appreciated by the people.

For instance, during the war there occurred in the line of duty more than three hundred casualties among the operators -from disease, death in battle, wounds, or capture. Scores of these unfortunate victims left families dependent upon charity, as the United States neither extended aid to their destitute families nor admitted needy survivors to a pensionable status.

The telegraph service had neither definite personnel nor corps organization. It was simply a civilian bureau attached to the Quartermaster's Department, in which a few of its favored members received commissions. The men who performed the dangerous work in the field were mere employees -mostly underpaid, and often treated with scant consideration. The inherent defects of such a nondescript organization made it impossible for it to adjust and adapt itself to the varying demands and imperative needs of great and independent armies such as were employed in the Civil War.

Moreover, the chief, Colonel Anson Stager, was stationed in Cleveland, Ohio, while an active subordinate, Major Thomas T. Eckert, was associated with the great war secretary, who held the service in his iron grasp. Not only were its commissioned officers free from other authority than that of the Secretary of War, but operators, engaged in active campaigning thousands of miles from Washington, were independent of the generals under whom they were serving. As will appear later, operators suffered from the natural impatience of military commanders, who resented the abnormal relations which inevitably led to distrusts were rarely justified, none the less they proved detrimental to the best interest of the United States.

On the one hand, the operators were ordered to report to, and obey only, the corporation representatives who dominated the War Department, while on the other their lot was cast with military associates, who frequently regarded them with certain contempt or hostility. Thus, the life of the field-operator was hard, indeed, and it is to the lasting credit of the men, as a class, that their intelligence and patriotism were equal to the situation and won final confidence.

| |

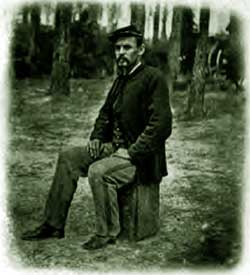

TELEGRAPHERS AFTER GETTYSBURG

The efficient-looking man leaning against the tent-pole in the rear is A.H. Caldwell, chief cipher operator for McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, Meade, and Grant. To him, just at the time this photograph was made, Lincoln addressed the famous despatch sent to Simon Cameron at Gettysburg. After being deciphered by Caldwell and delivered, the message ran: "I would give much to be relieved of the impression that Meade, Couch, Smith and all, since the battle of Gettysburg, have striven only to get the enemy over the river without another fight. Please tell me if you know who was the one corps commander who was for fighting, in the council of war on Sunday night." It was customary for cipher messages to be addressed to and signed by the cipher operators. All of the group are mere boys, yet they coolly kept open their telegraph lines, sending important orders, while under fire and amid the upmost confusion.

| |

|

|

|

Emergent conditions in 1861 caused the seizure of the commercial systems around Washington, and Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott was made general manager of all such lines. He secured the cooperation of E.S. Sanford, of the American Telegraph Company [(ATC)], who imposed much-needed restrictions as to cipher messages, information, and so forth on all operators. The scope of the work was much increased by an act of Congress, in 1862, authorizing the seizure of any or all lines, in connection with which Sanford was appointed censor.

Through Andrew Carnegie was obtained the force which opened the War Department telegraph Office, which speedily attained national importance by its remarkable work, and with which the memory of Abraham Lincoln must be inseparably associated. It was fortunate for the success of the telegraphic policy of the Government that it was entrusted to men of such administrative ability as Colonel Anson Stager, E.S. Sanford, and Major Thomas T. Eckert. The selection of operators for the War Office was surprisingly fortunate, including, as it did, three cipher-operators -D.H. Bates, A.B. Chandler, and C.A. Tinker -of high character, rare skill, and unusual discretion.

The military exigencies brought Sanford as censor and Eckert as assistant general manager, who otherwise performed their difficult duties with great efficiency; it must be added that at times they were inclined to display a striking disregard of proprieties and most unwarrantedly to enlarge the scope of their already extended authority. An interesting instance of the conflict of telegraphic and military authority was shown when Sanford mutilated McClellan's passionate despatch to Stanton, dated Savage's Station, June 29, 1862, in the midst of the Seven Day's Battles. [By cutting out of the message the last two sentences, reading: "If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or any other person in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army."]

Eckert also witheld from President Lincoln the despatch announcing the Federal defeat at Ball's Bluff. The suppression by Eckert of Grant's order for the removal of Thomas finds support only in the splendid victory of that great soldier at Nashville, and that only under the maxim that the end justifies the means. Eckert's narrow escape from summary dismissal by Stanton shows that, equally with the President and the commanding general, the war secretary was sometimes treated disrespectfully by his own subordinates.

|

|

|

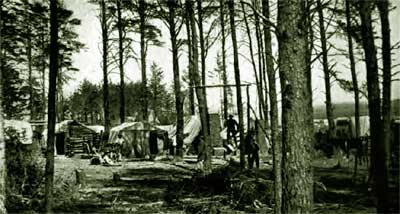

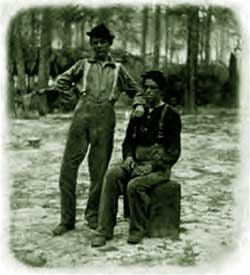

QUARTERS OF TELEGRAPHERS~PHOTOGRAPHERS

AT ARMY OF THE POTOMAC HEADQUARTERS

BRANDY STATION ~ APRIL 1864

It was probably lack of military status that caused these pioneer corps in science to bunk together here. The photographers were under the protection of the secret service, and the telegraphers performed a similar function in the field of "military information."

|

THE TELEGRAPHERS BOMB-PROOF

BEFORE SUMTER

It is a comfort to contemplate the solidity of the bomb-proof where dwelt this telegraph operator; he carried no insurance for his family such as a regular soldier can look forward to in the possibility of a pension. This photograph was taken in 1863, while General Quincy A. Gillmore was covering the marshes before Charleston with breaching batteries, in the attempt to silence the Confederate forts. These replied with vigor, however, and the telegrapher needed all the protection possible while he kept the general in touch with his forts.

|

|

|

|

|

One phase of life in the telegraph-room of the War Department- it is surprising that the White House had no telegraph office during the war- was Lincoln's daily visit thereto, and the long hours spent by him in the cipher-room, whose quiet seclusion made it a favorite retreat both for rest and also for important work requiring undisturbed thought and undivided attention.

Their Lincoln turned over with methodical exactness and anxious expectation the office-file of recent messages. There he awaited patiently the translation of ciphers which forecasted promising plans for coming campaigns, told tales of unexpected defeat, recited the story of victorious battles, conveyed impossible demands, or suggested inexpedient policies. Masking anxiety by quaint phrases, impassively accepting criticism, harmonizing conflicting conditions, he patiently pondered over situations-both political and military-swayed in his solutions only by considerations of vital national interest, with cabinet officers, generals, congressmen, and others. But his greatest task done here was that which required many days, during which was written the original draft of the memorable proclamation of emancipation.

Especially important was the technical work of Bates, Chandler, and Tinker enciphering and deciphering important messages to and from the great contending armies, which was done by code. Stager devised the first cipher, which was so improved by the cipher-operators that it remained untranslatable by the Confederates to the end of the war. An example of the method in general use, given by Plum in his "History of the Military Telegraph," is Lincoln's despatch to ex-Secretary Cameron when with Meade south of Gettysburg. As will be seen, messages written out for sending is as follows:

|

Washington, D.C. | July | 15th | 18 | 60 | 3 | for |

| Sigh | man | Cammer | on | period | I | would |

| give | much | to be | releived | of the | impression | that |

| Meade | comma | Couch | comma | Smith | and | all |

| comma | since | the | battle | of | get | ties |

| burg | comma | have | striven | only | to | get |

| the enemy | over | the river | without | another | fight | period |

| please | tell | me | if | you | know | who |

| was | the | one | corps | commander | who | was |

| for | fighting | comma | in the | council | of | war |

| on | Sunday | night | signature | A. Lincoln | Bless | him |

|

In the message as sent the first word (blonde) indicated the number of columns and lines in which the message was to be arranged, and the route for reading. Arbitrary words indicated names and persons, and certain blind (or useless) words were added, which can be easily detected. The message was sent as follows:

|

Washington, D.C.,July 15,1863

A.H. Caldwell, Cipher-operator, General Mead's Headquarters:

Blonde bless of who no optic to get an impression I madison-square Brown cammer Toby ax the have turnip me Harry bitch rustle silk adrian counsel locust you another only of children serenade flea Knox country for wood that awl ties get hound who was war him suicide on for was please village large bat Bunyan give sigh incubus heavy Norris on trammeled cat knit striven without Madrid quail upright martyr Stewart man much bear since ass skeleton tell the oppressing Tyler monkey.

Bates.

|

|

Brilliant and conspicuous service was rendered by the cipher-operators of the War Department in translating Confederate cipher messages which fell into Union hands. A notable incident in the field was the translation of General Joseph E. Johnston's cipher message to Pemberton, captured by Grant before Vicksburg and forwarded to Washington. More important were the two cipher despatches from the Secretary of War at Richmond, in December of 1863, which led to a cabinet meeting and culminated in the arrest of Confederate conspirators in New York city, and to the capture of contraband shipments of arms and ammunition. Other intercepted and translated ciphers revealed plans of Confederate agents for raiding Northern towns near the boarder. Most important of all were the cipher messages disclosing the plot for the wholesale incendiarism of leading hotels in New York, which barely failed of success on November 25, 1864.

| |

TELEGRAPH CONSTRUCTION CORPS

STRINGING WIRE IN THE FIELD

This corps was composed of about one hundred and fifty men, with an outfit of wagons, tents, pack-mules, and paraphernalia. During the first two years of the war the common wire was used; but when Grant set out in his Wilderness campaign, a flexable insulated wire was substituted. The large wire was wound on reels and placed in wagons, which drove along the route where the wire was to be erected. The men followed, putting up the wire as rapidly as it was unreeled. So expert were the linemen that the work seldom became disarranged. The first lines were constructed around Washington and to Alexandria, Virginia, in May. On the Peninsula the next year, the telegraph followed the troops in all directions. During the Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville campaigns it proved an unfailing means of communication between the army and Washington. As it was intended only for temporary use, the poles were not required to be very substantial, and could usually be found in the wooded Virginia country near the proposed route. The immense labor required in such construction led to the adoption of insulated wire, which could be strung very quickly. A coil of the latter was placed on a mule's back and the animal led straight forward without halting. While the wire unreeled, two men followed and hung up the line on the fences and bushes, where it would not be run over. When the telegraph extended through a section unoccupied by Federal forces in strength, cavalry patrols watched it, frequently holding the inhabitants responsible for its safety.

| |

|

|

|

Beneficial and desirable as were the civil cooperation and management of the telegraph service in Washington, its forced extension to armies in the field was a mistaken policy. Patterson, in the Valley of Virginia, was five days without word from the War Department, and when he sent a despatch, July 20th, that Johnston had started to reenforce Beauregard with 35,200 men, this vital message was not sent to McDowell with whom touch was kept by a service half-telegraphic and half-courier.

The necessity of efficient field-telegraphs at once impressed military commanders. In the West, Fremont immediately acted, and in August of 1861, ordered the formation of a telegraph battalion of three companies along lines in accord with modern military practice. Major Myer had already made similar suggestions in Washington, without success. While the commercial companies placed their personnel and material freely at the Government's disposal, they viewed with marked disfavor any military organization, and their recommendations were potent with Secretary of War Cameron. Fremont was ordered to disband his battalion, and a purely civil bureau was substituted, though legal authority and funds were equally lacking. Efforts to transfer quartermaster's funds and property to this bureau were successfully resisted, owing to the manifest illegality of such action.

Indirect methods were then adopted, and Stager was commissioned as a captian in the Quartermaster's Department, and his operators given status of employees. He was appointed general manager of United States telegraph lines, November 25, 1861, and six days later, through some unknown influence, the Secretary of War reported (Incorrectly, be it known), "that under an appropriation for that purpose at the last session of Congress, a telegraph bureau was established." Stager was later made a colonel. Eckert a major, and a few others captians, and so eligible for pensions, but the men in lesser positions remained employees, non-pensionable and subject to draft.

Repeated efforts by petitions and recommendations for giving a military status were made by the men in the field later in the war. The Secretary of War disapproved, saying that such a course would place them under the orders of superior officers, which he was most anxious to avoid.

| |

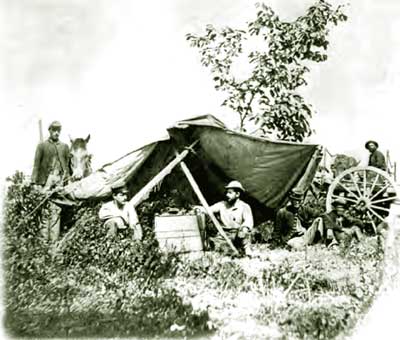

ONE OF GRANT'S

FIELD-TELEGRAPH STATIONS IN 1864

This photograph, taken at Wilcox Landing, near City Point, gives an excellent idea of the difficulties under which telegraphing was done at the front or on the march. With a tent-fly for shelter and a hard-tack box for a table, the resourceful operator mounted his "relay," tested his wire, and brought the commanding general into direct communication with separated brigades or divisions. The U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, through its Superintendent of Construction, Dennis Doren, kept Meade and both wings of his army in communication from the crossing of the Rapidan in May, 1864, till the siege of Petersburg. Over this field-line Grant received daily reports from four separate armies, numbering a quarter of a million men, and replied with daily directions for their operations over an area of seven hundred and fifty thousand square miles. Though every corps of Meade's army moved daily, Doren kept them in touch with headquarters. The field-line was built of seven twisted, rubber-coated wires which were hastily strung on trees and fences.

| |

|

|

|

With corporation influence and corps rivalries so rampant in Washington, there existed a spirit of patriotic solidarity in face of the foe in the field that ensured hearty cooperation and efficient service. While the operators began with a sense of individual independence that caused them often to resent any control by commanding officers, from which they were free under the secretary's orders, yet their common sense speedily led them to comply with every request from commanders that was not absolutely incompatible with loyalty to their chief.

Especially in the public eye was the work connected with the operations in the armies which covered Washington and attacked Richmond, where McClellan first used the telegraph for tactical purposes. Illustrative of the courage and resourcefulness of operators was the action of Jesse Bunnell, attached to General Porter's headquarters. Finding himself on the fighting line, with the Federal troops hard pressed, Bunnell, without orders, cut the wire and opened communication with McClellan's headquarters. Superior Confederate forces were then threatening defeat to the invaders, but this battle-office enabled McCellan to keep in touch with the situation and ensure Porter's position by sending the commands of French, Meagher, and Slocum to his relief. Operator Nichols opened an emergency office at Savage's Station on Summer's request, maintaining it under fire as long as it was needed.

One of the great feats of the war was the transfer, under the supervision of Thomas A. Scott, of two Federal army corps from Virginia to Tennessee, consequent on the Chickamauga disaster to the Union arms. By this phenomenal transfer, which would have been impossible without the military telegraph, twenty-three thousand soldiers, with provisions and baggage, were transported a distance of 1,233 miles in eleven and a half days, from Bristoe Station, Virginia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee. The troops had completed half their journey before the news of the proposed movement reached Richmond.

While most valuable elsewhere, the military telegraph was absolutely essential to successful operations in the valleys of the Cumberland and of the Tennessee, where very long lines of communication obtained, with consequent great distances between its separate armies. Apart from train-despatching, which was absolutely essential to transporting army supplies for hundreds of thousands of men over a single-track railway of several hundred of miles in length, an enormous number of messages for the control and cooperation of separate armies and detached commands were sent over the wires. Skill and patience were necessary for efficient telegraph work, especially when lines were frequently destroyed by Confederate incursions or through hostile inhabitants of the country.

| |

A TELEGRAPH BATTERY-WAGON

NEAR PETERSBURG, JUNE 1864

The operator in this photo is receiving a telegraphic message, writing at his little table in the wagon as the machine clicks off. Each battery-wagon was equipped with such an operator's table and attached instruments. A portable battery of one hundred cells furnished the electric current. No feature of the Army of the Potomac contributed more to its success than the field telegraph. Guided by its young chief A.H. Caldwell, its lines bound the corps together like a perfect nervous system, and kept the great controlling head in touch with all its parts. Not until Grant cut loose from Washington and started from Brandy Station for Richmond was its full power tested. Two operators and a few orderlies accompanied each wagon, and the army crossed the Rapidan with the telegraph line going up at the rate of two miles an hour. At no time after that did any corps lose direct communication with the commanding general. At Spotsylvania the Second Corps, at sundown, swung round from the extreme right in the rear of the main body to the left. Ewell saw the movement, and advanced toward the exposed position; but the telegraph signaled the danger, and troops on the double-quick covered the gap before the alert Confederate general could assault the Union lines.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

HEADQUARTERS FIELD-TELEGRAPH PARTY

AT PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA, JUNE 22, 1864

A battery-wagon in "action"; the operator has opened his office and is working his instrument. Important despatches were sent in cipher which only a chosen few operators could read. The latter were frequently under fire but calmly sat at their instruments, with the shells flying thick about them, and performed their duty with a faithfulness that won them an enviable reputation. At the Petersburg mine fiasco, in the vicinity of where this photograph was taken, an operator sat close at hand with an instrument and kept General Meade informed of the progress of affairs. The triumph of the field telegraph exceeded the most sanguine expectations. From the opening of Grant's campaign in the Wilderness to the close of the war, an aggregate of over two hundred miles of wire was put up and taken down from day to day; yet its efficiency as a constant means of communication between the several commands was not interfered with. The Army of the Potomac was the first great military body to demonstrate the advantages of the field telegraph for conducting military operations. The later campaigns of all civilized nations benefited much by these experiments.

| |

|

|

|

|

Of great importance and of intense interest are many of the cipher despatches sent over these lines. Few, however, exceed the ringing messages of October 19, 1863, when Grant, from Louisville, Kentucky, told Thomas "to hold Chattanooga at all hazards," and received the laconic reply in a few hours, "I will hold the town till we starve." Here, as elsewhere, appeared the anomalous conditions of the service.

| |

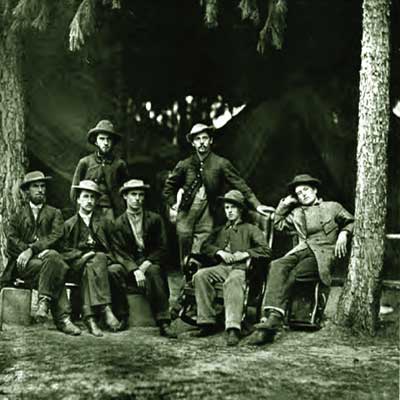

MEN WHO WORKED THE WIRES BEFORE PETERSBURG

These photographs of August, 1864, show some of the men who were operating their telegraph instruments in the midst of the cannonading and sharpshooting before Petersburg. Nerve-racking were the sounds and uncomfortably dangerous the situation, yet the operators held their post. Amidst the terrible confusion of the night assault, the last despairing attempt of the Confederates to break through the encircling Federal forces, hurried orders and urgent appeals were sent. At dawn on March 25, 1865, General Gordon carried Fort Stedman with desperate gallantry and cut the wire to City Point. The Federals speedily sent the message of disaster: "The enemy has broken our right, taken Stedman, and are moving on City Point." Assuming command, General Parke ordered a counter-attack and recaptured the fort. The City Point wire was promptly restored and Meade, controlling the whole army by telegraph, made a combined and successful attack by several corps, capturing the entrenched picket-line of the Confederates.

| |

|

|

|

While telegraph duties were performed with efficiency, troubles were often precipitated by divided authority. When Superintendent Stager ordered a civilian, who was engaged in building lines, out of Halleck's department, the general ordered him back, saying, "There must be one good head of telegraph lines in my department, not two, and that head must be under me." Though Stager protested to Secretary of War Stanton, the latter thought it best to yield in that case.

When General Grant found it expedient to appoint an aide as general manager of lines in his army, the civilian chief, J.C. VanDuzer, reported it to Stager, who had Grant called to account by the War Department. Grant promptly put VanDuzer under close confinement in the guardhouse, and later sent him out of the department, under guard. As an outcome, the operators planned a strike, which Grant quelled by telegraphic orders to confine closely every man resigning or guilty of contumacious conduct. Stager's efforts to dominate Grant failed through Stanton's fear that pressure would cause Grant to ask for relief from his command.

Stager's administration culminated in an order by his assistant, dated Cleveland, November 4, 1862, strictly requiring the operators to retain "the original copy of every telegram sent by any military or other Government officer...and mailed to the War Department." Grant answered, "Colonel Stager has no authority to demand the original of military despatches, and cannot have them." The order was never enforced, at least with Grant.

If similar experiences did not change the policy in Washington, it produced better conditions in the field and ensured harmonious cooperation. Of VanDuzer, it is to be said that he later returned to the army and performed conspicuous service. At the battle of Chattanooga, he installed and operated lines on or near the firing-line during the two fateful days, November 24-25, 1863, often under heavy fire. Always sharing the dangers of his men, VanDuzer, through his coolness and activity under fire, has been mentioned as the only fighting officer of the Federal telegraph service.

Other than telegraphic espionage, the most dangerous service was the repair of lines, which often was done under fire and more frequently in a guerilla-infested country. Many men were captured or shot from ambush while thus engaged. Two of Clowry's men in Arkansas were not only murdered, but were frightfully mutilated. In Tennessee, conditions were sometimes so bad that no lineman would venture out save under heavy escort. Three repair men were killed on the Fort Donelson line alone. W.R. Plum, in his "Military Telegraph," says that "about one in twelve of the operators engaged in the service were killed, wounded, captured, or died in the service from exposure."

| |

FRIENDS OF LINCOLN IN HIS LAST DAYS

MILITARY TELEGRAPH OPERATORS

CITY POINT IN 1864

When Lincoln went to City Point at the request of General Grant, March 23, 1865, Grant directed his cipher operator to report to the President and keep him in touch by telegraph with the army in its advance on Richmond and with the War Department at Washington. For the last two or three weeks of his life Lincoln virtually lived in the telegraph office company with the men in this photograph. He and Samuel H. Beckwith, Grant's cipher operator, were almost inseparable and the wires were kept busy with despatches to and from the President. Beckwith's tent adjoined the larger tent of Colonel Bowers, which Lincoln made his headquarters, and where he received the translations of his numerous cipher despatches.

| |

|

|

|

Telegraphic duties at military headquarters yielded little in brilliancy and interest compared to those of desperate daring associated with tapping the opponent's wires. At times, offices were seized so quickly as to prevent telegraphic warnings. General Mitchel captured two large Confederate railway trains bt sending false messages from the Huntsville, Alabama, office and General Seymour similarly seized a train near Jacksonville, Florida.

While scouting, Operator William Forster ontained valuable despatches by tapping the line along the Charleston-Savannah railway for two days. Discovered, he was pursued by bloodhounds into a swamp, where he was captured up to his armpits in mire. Later, the telegrapher died in prison.

In 1863, General Rosecrans deemed it most important to learn whether Bragg was detaching troops to reenforce the garrison at Vicksburg or for other purposes. The only certain method seemed to be by tapping the wires along the Chattanooga railroad, near Knoxville, Tennessee. For this most dangerous duty, two daring members of the telegraph service volunteered- F.S. Van Valkenbergh and Patrick Mullarkey. The latter afterward was captured by Morgan, in Ohio. With four Tennesseeans, they entered the hostile country and, selecting a wooded eminence, tapped the line fifteen miles from Knoxville, and for a week listened to all passing despatches. Twice escaping detection, they heard a message going over the wire which ordered the scouring of the district to capture Union spies. They at once decamped, barely in time to escape the patrol. Hunted by cavalry, attacked by guerillas, approached by Confederate spies, they found aid from Union mountaineers, to whom they owed their safety. Struggling on, with capture and death in daily prospect, they finally fell in with Union pickets- being then half starved, clothed in rags, and with naked, bleeding feet. They had been thirty-three days within the Confederate lines, and their stirring adventures make a story rarely equaled in thrilling interest.

Wiretapping was also practised by the Confederates, who usually worked in a sympathetic community. Despite their daring skill the net results were often small, owing to the Union system of enciphering all important messages. Their most audacious and persistent telegraph scout was Ellsworth, Morgan's operatpr, whose skill, courage, and resourcefullness contributed largely to the success of his daring commander. Ellsworth was an expert in obtaining despatches, and especially in disseminating misleading information by bogus messages.

In the East, an interloper from Lee's army tapped the wire between the War Department and Burnside's headquarters ar Aquia Creek, and remained undetected for probably several days. With fraternal frankness, the Union operators advised hime to leave.

| |

MILITARY TELEGRAPH OPERATORS

AT CITY POINT, AUGUST, 1864

The men in this photograph, from left to right, are Dennis Doren, Superintendent of Construction; A.H. Caldwell, who was for four years cipher clerk at the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac; James A. Murry, who as wire-tapper of Confederate telegraph lines accompanied Kilpatrick in his raid toward Richmond and down the Peninsula in February, 1864, when the Union cavalry leader made his desperate attempt to liberate the Union prisoners in Libby prison. The fourth is J.H. Emerick, who was complimented for distinguished services in reporting Pleasonton's cavalry operations in 1863, and became cipher operator in Richmond in 1865. Through Emerick's forsight and activity the Union telegraph lines were carried into Richmond the night after its capture. Samuel H. Beckwith was the faithful cipher operator who accompanied Lincoln from City Point on his visit to Richmond April 4, 1865. In his account of this visit, published in "Lincoln in the Telegraph Office," by David Homer Bates, he tells how the President immediately repaired to his accustomed desk in Colonel Bower's tent, next to the telegraph office, upon his return to City Point. Beckwith found a number of cipher messages for the President awaiting translation, doubtless in regard to Grant's closing in about the exhausted forces of Lee.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

WAR SERVICE OVER

MILITARY TELEGRAPH OPERATORS, JUNE 1865

"The cipher operators with the various armies were men of rare skill, unswerving integrity, and unfailing loyalty," General Greeley pronounces from personal knowledge. Caldwell, as chief operator, accompanied the Army of the Potomac on every march and in every siege, contributing also to the efficiency of the field telegraphers. Beckwith remained Grant's cipher operator to the end of the war. It was he who tapped a wire and reported the hiding-place of Wilkes Booth. The youngest boy operator, O'brien, began by refusing a princely bribe to forge a telegraphic reprieve, and later won distinction with Butler on the James and with Schofield in North Carolina. W.R. Plum, who wrote a "History of the Military Telegraph in the Civil War," also rendered efficient service as chief operator to Thomas, and at Atlanta. The members of the group are, from left to right: Dennis Doren, Superintendent of Construction; L.D. McCandless; Charles Bart; Thomas Morrison: James B. Norris; James Caldwell; A. Harper Caldwell, chief cipher operator, and in charge; Maynard A. Huyck; Dennis Palmer; J.H. Emerick; and James H. Nichols. Those surviving in June, 1911, were Morrison, Norris, and Nichols.

| |

|

|

|

|

The most prolonged and successful wiretapping was that by C.A. Gaston, Lee's confidential operator. Gaston entered the Union lines near City Point, while Richmond and Petersburg were besieged, with several men to keep watch for him, and for six weeks he remained undisturbed in the woods, reading all messages which passed over Grant's wire. Though unable to read the ciphers, he gained much from the despatches in plain text. One message reported that 2,586 beeves were to be landed at Coggins' Point on a certain day. This information enabled Wade Hampton to make a timely raid and capture the entire herd.

It seems astounding that Grant, Sherman, Thomas and Meade, commanding armies of hundreds of thousands and working out the destiny of the Republic, should have been debarred from the control of their own ciphers and the keys thereto. Yet, in 1864, the Secretary of War issued an order forbidding commanding generals to interfere with even their own cipher-operators and absolutely restricting the use of cipher-books to civilian "telegraph experts, approved and appointed by the Secretary of War." One mortifying experience with a despatch untranslatable for lack of facilities constrained Grant to order his cipher-operator, Beckwith, to reveal the key to Colonel Comstock, his aide, which was done under protest. Stager at once dismissed Beckwith, but on Grant's request and insistence of his own responsibility, Beckwith was restored.

The cipher-operators with the various armies were men of rare skill, unswerving integrity, and unfailing loyalty. Caldwell, as chief operator, accompanied the Army of the Potomac on every march and in every siege, contributing also to the efficiency of the field-telegraphs. Beckwith was Grant's cipher-operator to the end of the war, and was the man who tapped a wire and reported the hiding-place of Wilkes Booth. Another operator, Richard O'Brien, in 1863 refused a princely bribe to forge a telegraphic reprieve, and later won distinction with Butler on the James and with Schofield in North Carolina. W.R. Plum, who wrote "History of the Military Telegraph in the Civil War," also rendered efficient service as chief operator to Thomas, and at Atlanta. It is regrettable that such men were denied the glory and benefits of a military service, which they actually, though not officially, gave.

The bitter contest, which lasted several years, over field-telegraphs ended in March, 1864, when the Signal Corps transferred its field-trains to the civilian bureau. In Sherman's advance on Atlanta, VanDuzer distinguished himself by bringing up the field-line from the rear nearly every night. At Big Shanty, Georgia, the whole battle front was covered by working field-lines which enabled Sherman to communicate at all times with his fighting and reserve commands. Hamley considers the constant use of field-telegraphs in the flanking operations by Sherman in Georgia as showing the overwhelming value of the service. This duty was often done under fire and other dangerous conditions.

| |

A TELEGRAPH OFFICE

IN THE TRENCHES

In this photograph are more of the "minute men" who helped the Northern leaders to draw the coils closer about Petersburg with their wonderful system of instantaneous intercommunication. They brought the commanding generals actually within seconds of each other, though miles of fortifications might intervene. There has evidently been a lull in affairs, and they have been dining at their case. Two of them in the background are toasting each other, it may be for the last time. The mortality among those men who risked their lives, with no hope or possibility of such distinction and recognition as come to the soldier who wins promotion, was exceedingly high.

| |

|

|

|

In Virginia, in 1864-1865, Major Eckert made great and successful efforts to provide Meade's army with ample facilities. A well-equipped train of thirty or more battery-wagons, wire-reels, and construction carts were brought together under Doren, a skilled builder and energetic man. While offices were occasionally located in battery-wagons, they were usually under tent-flies next to the headquarters of Meade or Grant. Through the efforts of Doren and Caldwell, all important commands were kept within control of either Meade or Grant- even during engagements. Operators were often under fire, and at Spotsylvania Court House telegraphers, telegraph cable, and battery-wagons were temporarily within the Confederate lines. from these trains was sent the ringing despatch from the Wilderness, by which Grant inspired the North, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer."

During siege operations at Petersburg, a system of lines connected the various headquarters, depots, entrenchments, and even some picket lines. Connonading and sharpshooting were so insistent that operators were often driven to bomb-proof offices- especially during artillery duels and impending assaults. Nerve-racking were the sounds and uncomfortably dangerous the situations, yet operators held their posts. Under the terrible conditions of a night assault, the last despairing attempt to break through the encircling Federal forces at Petersburg, hurried orders and urgent appeals were sent. At dawn of March 25, 1865, General Gordon carried Fort Stedman with desperate gallantry, and cut the wire to City Point. The Federals speedily sent the message of disaster, "The enemy has broken our right, taken Stedman, and are moving on City Point." Assuming command, General Parke ordered a counter-attack and recaptured the fort. Promptly the City Point wire was restored, and Meade, controlling the whole army by telegraph, made a combined attack by several corps, capturing the entrenched picket line of the Confederates.

First of all of the great commanders, Grant used the military telegraph both for grand tactics and for strategy in its broadest sense. From his headquarters with Meade's army in Virginia, May, 1864, he daily gave orders and received reports regarding the operations of Meade in Virginia, Sherman in Georgia, Sigel in West Virginia, and Butler on the James River. Later he kept under control military force exceeding half a million soldiers, operating over a territory of eight hundred thousand square miles in area. Through concerted action and timely movements, Grant prevented the reenforcement of Lee's army and so shortened the war. Sherman said, "The value of the telegraph cannot be exaggerated, as illustrated by the perfect accord of action of the armies of Virginia and Georgia."

| |

THE TELEGRAPH CONSTRUCTION TRAIN, IN RICHMOND AT LAST

This train, under the direction of Mr. A. Harper Caldwell, Chief Operator of the Army of the Potomac, was used in construction of field-telegraph lines during the Wilderness campaign and in operations before Petersburg. After the capture of Richmond it was used by Superintendent Dennis Doren to restore the important telegraph routes of which that city was the center. In Virginia in 1864-5, Major Eckert made great and successful efforts to provide Meade's army with ample facilities. A well-equipped train of thirty or more battery-wagons, wire-reels, and construction carts was brought together under the skilful and energetic Doren.

| |

|

|

|

[The Editors express their grateful acknowledgment to David Homer Bates, of the United States Military-Telegraph Corps, manager of the War Department Telegraph Office and cipher-operator, 1861-1866, and author of "Lincoln in the Telegraph Office," etc., for valued personal assistance in the preparation of the photographic descriptions, and for many of the incidents described herein.]

Hand Coded by Mark C. Hageman for The Signal Corps Association 1860-1865, Excerpts from "The Photographic History of the Civil War" published in 1911

|

|